3 Myths About Buck Rubs

A deer rubs his antlers on a small tree to mark his territory right? How complicated can that be? Well, here are some things that will shed new light on what rubs actually mean. By Bernie Barringer Outdoor writers like myself are always looking for new ideas and new things to write about. We are always analyzing what we see and trying to learn more from each nugget of bucks sign, mostly in the hopes that we can learn something which we can pass along to our readers in order to educate them and help them hunt more effectively. That’s all good. The bad side of the coin is that we also tend to overthink and overanalyze things from time to time. In our zeal to learn more that we can write about, we sometimes read way too much into what we are seeing. I think that is true with much of what has been written in the outdoor magazines about rubs in the past 20-30 years. There are even books about how finding rubs lined up in one direction can lead you to your next big buck. Well, let’s just say that’s a stretch. The advent of GPS collars that track the movement and activities of bucks 24/7 has added to our knowledge of deer behavior, but it has also turned some long-held beliefs into rubbish. Some of those beliefs are related to how deer make and use rubs. Here are three myths that we can put to rest. Rubs are Territorial Markers If bucks were patrolling a territory, making rubs to mark the edges of their range, the GPS tracking data would bear that out, but it does not. There is no evidence whatsoever that bucks even have a territory they try to protect in any way. They do have home ranges—areas where they spend the majority of their time—but they show no evidence that they try to protect that home range from other deer in any way. That’s not to say that rubs are not forms of communication; however, because they are. When the bucks rub trees they deposit scent on them, which communicates to the other deer in the area the statement that, “I was here.” But really, not much more than that. It’s a way for deer to get to know each other better and have a feel for who is using the same areas they are using. Velvet Shedding Rubs Some deer authorities have surmised that different rubs at different times of the year and on different sizes of trees can be filed into certain categories, such as Velvet Shedding rubs, Signpost Rubs, even Rutting Rubs. Possibly the most misunderstood is the belief that bucks use rubs to remove the velvet from their antlers. First, it’s important to understand that when the velvet dries, it will fall off whether they rub it on something or not. Secondly, if a buck is inclined to remove it, it wouldn’t make much sense for him to use the trunk of a small tree to remove it. Some bucks don’t seem to care much unless the velvet is hanging down impairing their vision, while others seem to aggressively work at tearing it off. A friend once watched a full velvet whitetail walk by just out of range on September 5. He sat in a ground blind and watched that deer walk right up to a leafy bush and stick his antlers right into the brush. The buck twisted and turned the antlers in the brush, then slashed at it from side to side a few times, completely removing every trace of bloody velvet within 60 seconds. Bucks may remove some of the velvet from their antlers by rubbing on tree trunks, but that’s not the preferred method. Only Big Bucks Rub Big Trees This has an element of fact in it because larger bucks do tend to rub larger trees than smaller bucks at time. But that’s about all there is to it. Biologists have theorized that one of the reasons bucks rub trees is to exercise their neck muscles for the battles that will occur during the rut. It stands to reason that a buck would choose a tree that has some flex too it so it “fights back” so to speak. Larger, stronger bucks would naturally choose thicker trees to create the exercise needed. Certainly, a tree that is really shredded was rubbed by a big buck because small bucks simply do not have the antler size and physical power to really tear up a tree the size of your wrist. I have personally witnessed small and large bucks rub trees of any size. I have even seen them rub fenceposts and power poles that had no give at all to them. Some of these have been called signpost rubs. They can be rubbed by the biggest buck in the area one minute and then a spike the next. Signpost rubs are rubs that get used from year to year and are often on big trees. It seems like every deer that comes along, no matter the size, can resist giving it a stroke or two. These don’t seem to be chosen for any specific reason other than the fact that they are in a spot where a lot of deer go by. And that in itself has some value to the hunter. So don’t read too much into what you see in a rub. In fact, if you really want to learn a lot about who is using a particular rub, put a game camera on it. Seeing is believing.

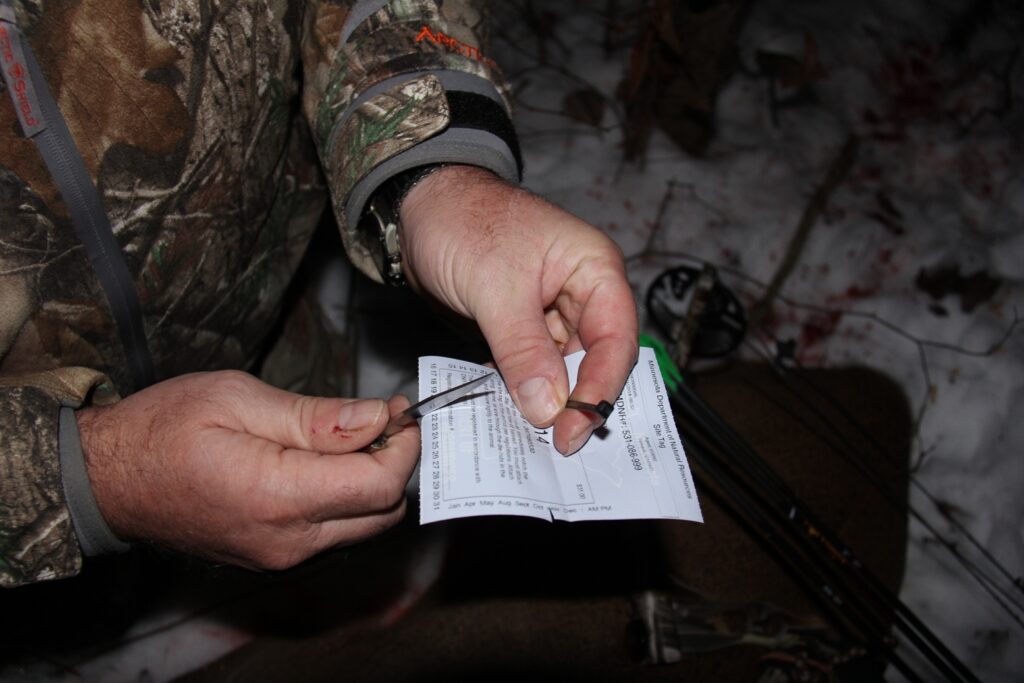

How State Agencies Estimate Deer Populations

All states publish stats for their deer herds including overall populations and trends. How they arrive at these numbers might surprise you. By Bernie Barringer Like me, no doubt you have marveled at the numbers being thrown about by state game agencies when it comes to their deer populations and harvest management objectives. One state agency may say they have a million deer and three years later they say they have 875,000. Another state may say they have 480,000, which is up from 425,000 just three years previous. Where do they get these numbers? Sometimes it seems as if they just grab them out of the air or take them from some computer model. Often, our personal observations do not seem to match the numbers being put forth by the state agency. Let’s take a look at how most state agencies arrive at these numbers and then how they adjust these numbers based on trends. How many deer are there? To recognize trends in population dynamics, there must first be a baseline. Researchers need a number to start with. Something called “Random Sampling” doesn’t really sound like science, but it is. Let’s say a team of surveyors goes out in each county in the state and spotlights likely looking deer habitat for four hours. There is one team per county and each team spotlights fields in about ten percent of the county. They count every buck and doe they see. This is a random sample and it can be extrapolated with remarkable accuracy. Since ten percent of the areas were counted, you can take the count times ten and you have a reliable estimate of the number of deer in the state. This 10 percent count has less than a 2% statistical margin for error. But they do not end it there. Most states also use random sampling in aerial surveys, where they fly over areas during the winter and count deer as they show up well in the snow. If you have never tried this you would be shocked at how well you can see them. Some states have also used counts of deer droppings in wintering areas, roadkills and other methods of estimating deer populations. More recently, scouting cameras are being used to tighten up the data. The more data that is collected, the more reliable the estimates become. Done for just one year, these surveys are quite reliable, but combine and average the data for ten years, or 20 and you have some pretty accurate numbers. However, many things can change the numbers. Harsh winters, disease, drought, overharvest, predators, etc. can all cause significant upturns or downswings in populations. These trends are followed closely by including factors such as fawn recruitment rates, significant changes in survey numbers and harvest reporting. Fawn Recruitment Rates Understanding fawn recruitment rates has proven to be one of the best indicators of population trends and their causes. Fawn recruitment–the number of young deer in the population—can be tied to predation and habitat quality. When fawn recruitment rates plummet, it’s usually either a bad year for food availability or a rise in predator populations. In some areas, predators are taking up to 80 percent of the fawns from the deer population. Poor pelt values for coyotes is one of the reasons, as coyote populations are high in many areas of North America. Bobcats, bears and wolves are taking a big toll in some areas as well. The surveys described above are indicators of low fawn recruitment, but the best indicator is the number of young-of-the year deer in the harvest. Most adult does will produce two fawns under normal habitat conditions. About 50 percent of the yearling does breed, and they average about one fawn. These numbers can be used to estimate the number of increase in young-of-the-year deer in the harvest. Of course, a relatively small number of fawns actually make it until the fall hunting season. When fawn recruitment rates are near .75-1.00, the herd is healthy and growing. Some states record negative numbers in fawn recruitment, which means the overall population is dropping. Surveys Road kills, spotlight surveys, aerial surveys, and other methods help determine the overall population, but more importantly, they help identify trends in the population. When the number of deer is down in a spotlight survey, for example, and the number of roadkills dropped, biologists have a indicator that the population is dropping. Of course other factors can influence these numbers. Poor weather or fog on a spotlighting night can skew the numbers. Lack of snow in aerial surveys can make for poor deer counting conditions. All these things are taken into consideration when the numbers are tabulated, but as you can imagine, this is an inexact science. Biologists must do the best they can with the data they can gather. The more data sources available, the more accurate the numbers will be. Reporting Fawn recruitment rates and population trends can be very strongly influenced by harvest statistics. As more states agencies have begun to understand the value of harvest numbers in estimating populations and population trends, they have gone to mandatory reporting. Check stations, online reporting and phone reporting are options in most states. About 2/3 of states now have mandatory reporting for deer harvest. The other 1/3 use surveys. These surveys are phone calls or mailings that ask the hunters to report their seasonal success. Mandatory reporting is only as good as the enforcement and many hunters do not report their harvested deer. Agencies use a correction factor to estimate the number of hunters who do not report, then add that correction into the overall tally. Voluntary sampling is nearly as effective, remember, just a 10% response has a statistical error of less than 2%. These voluntary harvest surveys and mandatory reporting have significant value in establishing trends. By learning if the deer killed was a doe or buck fawn, biologists can learn important data in fawn recruitment, for example. Without question, no one

The Four Parts of a Successful DIY Mentality

By Bernie Barringer Hunting away from home presents some unique challenges. When you are hunting in your home area, you have an entire season to bag your buck and fill out your deer tags. But on a DIY road trip, you are hunting under a deadline; you have a limited amount of time to get the job done. The situation calls for an entirely different set of strategies and actions. We can break the hunt down into four separate factors that can significantly improve your chances of success. Scout Thoroughly Back home, you have a pretty good feel for the deer movement patterns. You know where they tend to bed and where they tend to feed and at least a general idea of how the move between the two. When you arrive at a new hunting area on a DIY hunt, you must learn as much as you can in a short period of time. The greatest mistake most hunters make is to climb into a stand too early. You may find an area that’s all torn up with rubs and scrapes or a beaten down deer trail and you can’t wait to get a treestand set up and start hunting. That can be a big mistake, because you may lack confidence in your spot. It’s a lot easier to sit all day when you have confidence in your spot, and that confidence comes only from thorough scouting. Hunt Aggressively Hand in hand with an exhaustive scouting is the desire to make important decisions on the fly and be very aggressive in your hunting. Back home, you would never walk right through a bedding area, but on a road trip you might need to know where the deer are bedding and what is available to you. Spray down the lower half of your body with Scent Killer to minimize your ground scent then go right in there to look it over. Get some game cameras out and check them often so you have a good feel for the area’s potential. It’s hard to beat a game camera on a primary scrape with some fresh urine or an estrus lure. You must take calculated risks and force the issue. If you wait for the information to come to you, you may run out of time, you must go get it. Hunt in Any Conditions Rain or shine, you must be out there to make it happen. I have done more than 20 DIY road trip hunts in several states and it seems like it usually comes down to one or two stands where I feel like I am going to be successful if I just put in my time. Take the appropriate clothing for any conditions and gut out the tough times. Each time you hunt, you have a chance. If you are sitting in a motel waiting for the snow to stop or the wind to change, you are more than likely going to go home with an unfilled tag. Be Mobile Right along with hunting aggressively and hunting hard is the willingness to move quickly and adapt to changing conditions. On one hunt in Iowa, I felt like I was about 60 yards off target, so I climbed down and moved my entire set up the hill. I killed a mature buck the next morning from that tree and I would have helplessly watched him walk by if I had not moved. If you sense that you need to make a move, or feel that a wind switch may betray you, don’t wait, make your move NOW. Using equipment that is light and easy to put up and down is a real key to being mobile. Keep these four factors in mind on your next DIY hunt and you will increase your odds of coming home with a buck in the back of the truck instead of a tag in your back pocket.

Do These 5 Things This Summer to Help You Shoot a Buck in the Fall

Don’t wait until the last minute. You can increase your chances of shooting a nice buck this fall by doing some preliminary work in the summer. By Bernie Barringer If you’re sitting here reading this deer hunting magazine in the summer, I’d say it’s safe to assume you’re a pretty serious deer hunter. Like most deer hunters, I think about whitetails year ‘round, but most of my preparation and scouting activity is done just before the season opens. Most years I hunt from opening day right through the final bell. However, these days I find myself involved in deer hunting tasks year ‘round, especially in the summer. I like fishing as much as the next guy, probably way more than most, but I believe it’s really important to take a few days to concentrate on hunting chores during the summer months. I have found that there are a few specific things I can do during the dog days of summer that will significantly up my odds of shooting a buck in the fall. Preseason work has been paying off big for me. I have gone into each hunting season feeling much more prepared and confident that ever before and my success, especially in the early season, but really all season long, has proved the value of this preseason work. I encourage you to take some time to do these five tasks and I think you will agree that they are well worth it. Trim shooting lanes Saplings and brush grows up around your treestands every year. If you wait till the last minute to trim it, you may alert the deer to your presence. They know their woods intimately, and some fresh cut trees lying around right before the season opens might put a mature buck on edge. In the summer, you don’t have to worry about drops of sweat on the ground and you can pile the trimmings in a way that will move the deer past your stand. Using a pile of brush to gently guide movements only works if it has been done well ahead of time. Some of these subtle brush piles can make the difference between having a deer move past your stand out of range versus have the buck you want standing right in your shooting lane. This guiding doesn’t have to be a big operation. Even a couple limbs can cause the deer to alter their movement by walking around them rather than pushing through. On private land with permission, you can even hinge-cut a tree and drop it across a trail to block it. Improve bedding areas My friend and Iowa big buck nut Jon Tharp taught me this one, although he says it didn’t originate with him. During the winter, Jon does his hinge cutting to improve the amount of sunlight getting to the forest floor, but in the summer, he actually creates deer beds. That’s right, individual beds where he wants the deer to lie down. Bucks do not like to lay on sticks and stones, so you can make a nice bed with a rake by clearing out a small area. Bucks like to put their back against some kind of structure just like a big bass would, so deer beds are best made with some kind of cover next to it. A downed log or deadfall tree is great; a small brushpile works as well. Bucks will bed down where they feel secure and you can create a feeling of security for them that will keep them from wandering over to the neighbors by making a group of individual beds that allow them to see what’s in front of them and have a barricade behind them. By doing several at differing angles, you allow the buck to use the one he prefers in various wind directions. Plant a throw-and-grow brassica food plot You don’t have to be a farmer to plant a food plot. There are a couple simple tactics that work very well with little effort. You can till up a small clearing in the woods and rake in some brassica seeds. Plants like turnips, kale, forage rape, sugar beets and radishes all work really well. The best time to do this is early August right before a rain. Deer do not pay much attention to these plants as they grow throughout the late summer into early fall so they have time to become established. But once cold weather arrives, the deer pound them. These plants become more palatable after a hard frost turns the starches in them to sugar. The deer are piling into them during the early archery season. Perfect timing. Strike right away because they get cleaned up quickly. Another easy plot can be created if you have a treestand on the edge of a crop field. By raking these seeds right between the rows of corn or soybeans in front of your treestand, you’ve created a mini food plot of your own. OF course, if you don’t own the land, you’ll need permission, but most farmers will allow this. The might look at you a little funny until they see the results, but it can’t hurt to ask. When the corn or beans are harvested, the brassicas are sitting there ready for the hungry deer. With the right planting timetable, these little secret spots are often at their peak in perfect timing for the October archery seasons. Keep those scouting cameras working Far too many hunters wait until just before hunting season to put out their scouting cameras. I have a half-dozen cameras working all summer. I have them on mineral sites and in bedding areas. Not only is it fun to watch the bucks’ antlers grow and the fawns rapid daily maturing, but you can learn a lot about the deers’ preferred travel corridors. This is important information that will help you pattern the deer later on. In the summer, you can be a little more aggressive about moving about in

Quest for a Color Phase Bear

May bear hunters are interested in shooting a big mature bruin, but more and more bear hunting enthusiasts are looking to add a color phase bear to their collection. By Bernie Barringer Black bears are one of our most sought after big game animals in North America because they offer so many different opportunities and styles of hunting. Bears rarely harm humans, but the fact that the bear is a predator which could really mess you up adds the appeal and the adrenaline value of hunting them. One of the most fascinating things about black bears in North America is the phenomenon that they are not all black in color. Black bears come in a variety of colors that are loosely grouped into four major categories: Blonde bears are characterized by yellow to a very light brown color and may have darker colored legs and head. Cinnamons are a brownish-red color showing a distinct reddish tint characteristic of the spice after which it is named. In some areas these bears are called red bears. Brown, normally called chocolate to distinguish them from Alaskan brown bears, can range from fairly light brown to a deeper, chocolate brown color. Dark chocolates are the most common color other than black. Bears with jet black fur are the most common and have the unmistakable pure black fur with often a shiny black sheen. Blacks commonly have a white blaze on their chest in some locales, while bears of other colors rarely do. There are other colors that show up in tiny geographic areas such as the Kermode Bear and the Glacier bear, but for the common man who would like to collect a bear of several colors, these four color phases—black, brown, cinnamon and blonde–represent the opportunities available to us. A growing number of people are showing an interest in shooting a bear of a color other than black and I am one of them. I am aware of a very small number of people who have harvested one of each of the four major color phases. I have taken three of the four color phases and I am up for the challenge of taking the hardest of them all, the blonde phase black bear. I arrowed the cinnamon bear on a hunt with Thunder Mountain Outfitters in Saskatchewan during the spring of 2014. I have been working on getting the blonde for three years now. I would have bagged them all, but for the commitment I have made to myself to shoot one of each with a bow. Why would anyone want to go to the trouble to shoot one bear of each color phase? Well, why do we have Pope & Young and Boone & Crockett record books? By our very nature, hunters are collectors; we like to add things to our collections and keep track of things like size, color and other characteristics. There are plenty of benchmarks to strive towards. Some people really want to get 500-pound bear, some want to get a B&C bear, some want one with a nice blaze on the chest and some want a bear of a different color. It’s a part of who we are as hunter-gatherers and collectors. And it’s an important part of why bear hunters love bear hunting. Deer hunters, for example, have little to go on by comparison. We measure antlers by the inch and in some areas deer are weighed and recorded. That’s pretty boring when compared to the benchmarks bear hunters have. Interestingly, the vast majority of black bears of a color other than black are found west of the Mississippi river. There are tiny populations of brown bears in eastern Minnesota and western Wisconsin, for example, but nothing like the numbers of color bears of the west. It’s estimated that about 5% of the bears in Minnesota are brown with the majority found in the northwestern corner of the state. Western Ontario contains a small number of brown colored bears as well. Farther south, Arkansas and Oklahoma produce a little higher percentage of brown bears and even the occasional cinnamon. This is in keeping with the general trends that the farther west and south you go in North America, the greater the instance of color bears and the lighter the colors. This is a mystery but maybe someday a DNA study will be done and shed some light on this puzzle, but in the meantime, most of us are happy to have the variety and the challenge these western color bears offer. So let’s take a look at the four major colors and divide them up geographically. If you are on a quest for a bear of one of these colors, this should help you narrow your search. Blacks, of course, are found across the eastern US and Canada. Rather than explain where they are common, it’s easier to explain where they are uncommon. Across the western US they run about 50 percent and in some states less. Black bears are less common in Canada in the Rocky Mountains in Alberta and British Columbia where increasing numbers of browns cinnamons and the occasional blonde may be found. States such as New Mexico, California, Colorado, Utah and Arizona have fewer blacks than other colors. In Washington and Oregon, they run about 50% with other colors. Black bears run at least 40-50% across the northern territories of Canada, and then become scarce in Alaska where once again most of the bears are black. The Northwest Territories has fewer black bears than the Yukon, showing a trend towards color that reverses itself as it gets closer to Alaska and the west coast of British Columbia. The coastal areas and islands of Canada have bear populations consisting of nearly 100% black bears except for the pockets of Kermodes and Glacier bears found in BC and Alaska. Brown bears are the second most common color phase. I mentioned western Ontario and Northwest Minnesota, which is the eastern end of the range