A Well-Traveled Grizzly Bear’s 5,000-Mile Journey

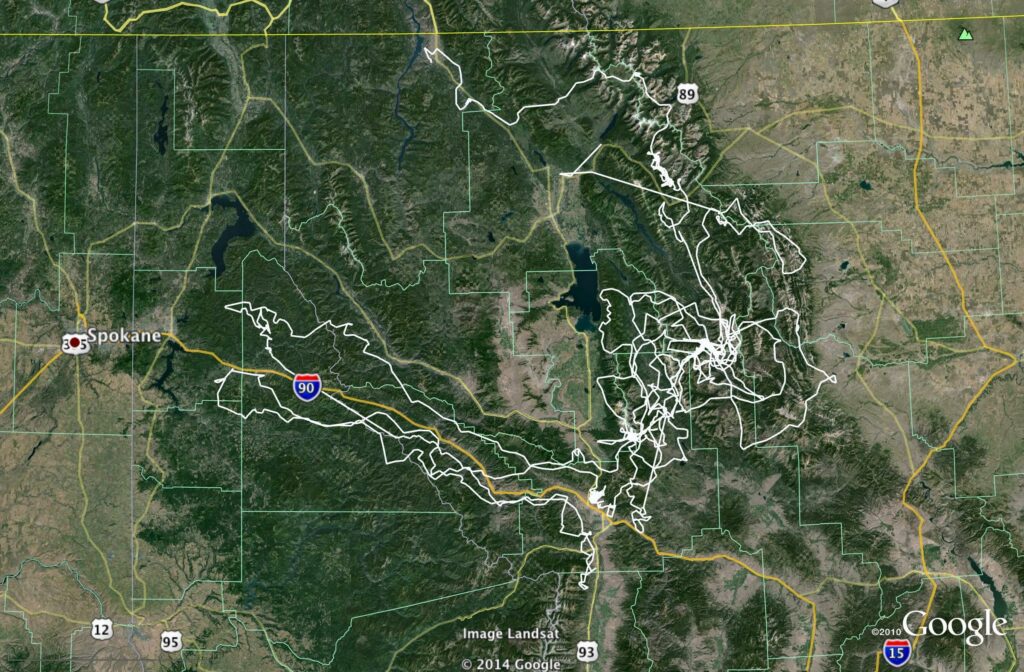

Courtesy Idaho Public Radio One grizzly bear’s incredible 5,000-mile journey across Montana and Idaho has scientists re-thinking what they know about the animals. Ethyl the grizzly bear was 19 years old when she started out on her epic journey over 5,000 miles in two years.CREDIT U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Ethyl the grizzly bear walked from Kalispell, Mont. west toward Coeur d’Alene and back east toward Missoula. She covered thousands of miles of mountainous terrain in just two years, and scientists are still trying to figure out why. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service grizzly bear recovery coordinator Chris Servheen says Ethyl’s story began when she was first captured in 2006 east of Kalispell, Mont. “She was eating apples near somebody’s house,” Servheen says. “To keep her out of trouble, we captured her and moved her. She basically stayed right in that same area, she stayed out of trouble.”ListenListening…5:03Click play to hear Samantha Wright’s conversation with Chris Servheen. They captured her again in 2012 along with her cub, close to the first site, again eating apples. She was moved again, this time about 30 miles away, and biologists put a tracking collar on Ethyl. Servheen says that’s when 19-year-old Ethyl’s epic journey began. “She started traveling all through the northern continental divide grizzly bear ecosystem.” Her collar recorded a distance of about 2,800 miles between the individual locations, which are recorded every six hours. Servheen says, “she certainly went a lot farther than that, because those are just straight line distances, so she probably went well over 5,000 miles in two years. She sure covered a lot of ground.” Here’s a map of Ethyl’s movements over the last two years, as tracked by her radio collar.CREDIT U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Servheen has been studying bears for 34 years. He says Ethyl’s is the longest journey he’s ever seen undertaken by a grizzly bear. “She was in really remote country quite a bit of the time, and then sometimes she was very close to people,” says Servheen. But he says Ethyl never had a run in with humans, and she crossed several roads and highways without incident. The big question is why was she traveling so far from her home range. Servheen says scientists don’t have a clue. “She was minding her own business, just looking around. Why she did this and what she was looking for, we don’t know, it’s a mystery. She’s a traveling bear, that’s for sure.” He says Ethyl took a strange route, too. “It’s almost like she was looking for something, but I have no idea what she would be looking for,” Servheen says. “I just can’t explain it. It’s a new one on us.” Ethyl’s remarkable journey is teaching scientists new things about bears. Servheen says she’s taught him “that we need to know more about how bears move across the landscape.” He says biologists learn something new every time they collar a bear. But “Ethyl’s movements really don’t fit into any previous pattern we’ve seen before,” says Servheen. “Whether this is something that happens more often than we think, I suspect not. I think what Ethyl was doing was something unique to her and why she was doing it, there’s no real rational reason that we can understand why she did this.” But, he says, “it’s good to have a little mystery out there.” Servheen says Ethyl’s collar fell off this year, so they’re not sure where she is now. But he hopes she’s sound asleep in some warm den “somewhere up in the mountains under the snow. I hope that when she comes out next spring she settles down and continues to live successfully, and has cubs.” Do you have an opinion on what caused this bear to travel so far? Leave your comment below.

3 Ways to Thief-Proof Your Scouting Cameras

Possibly the only thing that hurts worse than losing a trail camera to a thief is losing the information it contained. Here are three ways to minimize your losses. By Bernie Barringer The sick feeling in the pit of my stomach turned into anger as I stood there looking at the tree my scouting camera had been attached to the previous day. I hate losing a trail camera to a thief, but trail cameras can be replaced. What really made me angry was losing the information contained on the SD card. I was hundreds of miles from home on a DIY deer hunting trip. The cameras I put out were a huge part of my decision-making process regarding where I would hang my stands and hunt. I had just lost an entire 24 hours of information about the deer in this area. That really hurts. I run a lot of scouting cameras, it’s almost like a sport in itself for me. I use them not only for deer hunting, but for bear hunting, property surveillance, wildlife viewing, even predator monitoring and control. I put them in areas where I don’t expect anyone to every find one, and at times I put them in areas where I figure others will see them and hope they leave them alone. Still, the number of cameras I have had stolen over the years could be counted on my fingers. However, I have begun to take some precautions to avoid losing them to thieves. Here are three ways to minimize your losses. Go Covert One of the easiest ways to cut losses is to simply use cameras that are harder to see and hide them better. There are three primary kinds of flashes for night photos, white flash, infrared and black flash. Black flash cameras do not have a flash that is visible to the eye. Both white flash and IR cameras have lights that can be seen by anyone who happens to be looking the right direction when they take a photo. Larger cameras are easier to spot than smaller ones. Many companies are making very small camera bodies that are not much bigger than your hand. Small black flash cameras are difficult to detect, but I go one step farther. I will use a small bungee cord to secure a leafy branch over the camera, just leaving enough opening for the sensor, the lens and the flash. They become difficult to see unless someone is actively searching for them. Put Them Out of Reach One of the most effective ways to thwart thieves is to put the camera up where they cannot reach it. I like to hang the camera at least ten feet off the ground and point it downward to monitor the area. Some people might be able to shinny ten feet up into a tree to get the camera, but most won’t. There are several companies that make mounts for cameras that work in this way. The two I have used are the Covert Tree-60 and the Stic-N-Pic. Here’s how I go about it. I carry a climbing stick to the location I want to put the camera. Just one. I can strap the climbing stick to the tree, climb up it, and reach at least ten feet off the ground to mount my camera. When I am done, I just take the stick out with me. It’s not a totally fool proof way to get the camera out of reach, but it works. Here’s a video showing how I do this. Putting cameras up high comes with another advantage: deer do not seemed to notice the flash at all. I have seen some deer become alarmed by a white flash at eye level, but I have never seen a case where a deer reacted in a negative way to a flash ten feet up. Lock Them Up Most camera companies are now making lock boxes for their cameras. This was at first a response to the fact that bears like to chew on scouting cameras, but it works equally well to discourage the camera thief. These steel boxes can be bolted to a tree and then the camera is locked securely inside the box. Here’s a video of how I use these at bear baits. The disadvantages of this strategy include the extra weight of carrying the steel boxes with you, and the extra tools needed to fasten it to the tree. I have a separate backpack that I use which contains these boxes, lag bolts, padlocks and a cordless screwdriver with a socket. (Putting a screw in a tree on public land is not legal in some states; it is your responsibility to know the laws.) I use the cordless screwdriver to fasten the box to the tree with lag screws, insert the camera and then lock it up. It’s really not that much extra work and this makes it very difficult for any would-be thief to make off with your camera unless the creep returns with a saw and cuts down the tree. With a little extra effort, you can protect your cameras from thieves and get the photos you desire. Each of these three methods has its time and place.

6 ways Spring Scouting Means Big Fall Bucks

A serious hunter’s work is never done. Springtime is one of the best times of the year to get out in the woods and learn some things about your hunting area that you couldn’t learn at any other time of the year. By Bernie Barringer Springtime is not just for fishing and turkey hunting. Serious whitetail hunters crave opportunities to learn more about whitetails year-‘round, and I’m one of them. Those first nice days of spring when the snow melts off and the woods are coming alive with life once again are great times to get out to the properties you hunt and look them over. You will be surprised at what you will learn. Here are six reasons I like prospecting for bucks in the springtime. Spring scouting helps me learn how deer use terrain features. During the fall, leaves are dropping, which covers up a lot of the sign. Trails that are indistinct during the late summer and fall are glaringly obvious during the spring before plant growth is working against you. Deer tend to follow the same terrain features generation after generation, and the springtime is the best time to get out there and see where the well-worn trails are found. You will not only learn things about their travel patterns on that particular property, but you will learn things about how deer use the topography and terrain that will help you diagnose the movement on other properties. Scrapes, rubs and other rut sign is still there and easy to see. Now is the time to spend analyzing how the rubs are laid out in a specific pattern. In the fall, you walk right by them because you want to spend your time hunting. In the spring, you can really work the puzzle out. Take note of which side of the tree they are on and see if several rubs line up with the markings on the same side of the tree. You have just found a buck’s travel way. Signpost rubs and groupings of scrapes show you where a buck spends a lot of his time. Collections of several rubs in one small area may indicate a preferred bedding area. Bucks tend to rub a few trees when they rise from their beds in the afternoon, and their sanctuaries will often have several dozen rubs in less than an acre. A spot like this could be a gold mine come fall. In the spring, you can walk right into the bedding areas and sanctuaries without worry about damaging your hunting prospects. You would never walk right into the deer’s bedding area during the hunting season for fear of moving the bucks entirely out of the area. No such worry in the spring because your intrusion will be long forgotten by the season. Wade right in and look it over good. Make some improvements by hinging a couple trees and piling up brush. I know one hunter who carries a bag of grass seed and seeds good bedding cover as he scouts these areas. Combine your scouting with shed antler hunting. Keep in mind that the place a buck drops his antlers may have little to do with his fall patterns, because his winter patterns revolve around food, whereas the fall patterns revolve more around interactions with does and other bucks. But picking up shed is fun and it allows you to get an idea which bucks made it through the winter. Spring is the time to put out mineral licks. I put out mineral as soon as the show is off the ground and the deer use the mineral licks all through the spring and summer. The mineral not only offers the deer healthy diet enhancement, but it allows you to inventory the deer with trail cameras placed at these mineral sites. One good mineral lick maintained regularly should be on each piece of property, and for large properties over 300 acres, two sites is even better. Once you have found great looking places to hunt with lots of deer activity, put up some treestands. Putting up stands and trimming shooting lanes in the spring offers the chance to spend the necessary time in the woods without the worry of leaving human scent all over the area. By putting up stands early, there is plenty of time for the scent intrusion to dissipate. Your cuttings, tracks, trimmings and markings are long forgotten by fall. You may have found a place that will be a great hunting location year after year, now is the time to get a stand in position and take advantage of it. So take some time out from fishing or turkey hunting this spring and get into the woods. The work you do now might make the difference between holding a nice buck in a photograph versus holding an unfilled tag come next fall.

The Science of Scents: How Well Can Deer Smell?

The sense of smell among members of the deer family is legendary. In fact, it’s hard for humans to grasp. But recent research into the sense of smell of elk and whitetails finally puts some numbers to it. By Bernie Barringer I was aroused from my calm, patient state by a flicker of movement to my right. I slowly turned my head and saw a buck approaching at a slow walk. Suddenly at full alert, I started looking for an opportunity to get my bow off the hanger as the mature buck closed the distance. When he stopped and looked away, I got my bow in hand and ready to draw. This buck was really nice, and my heart began to pound. When the buck was 15 yards away, he stopped and froze. His demeanor changed as he dropped his head to the ground and sniffed the trail in front of him. In an instant, he had gone from relaxed to tense. He paused for a few seconds and then took three steps backwards before turning, lowering his head, and disappearing into the forest. Clearly he had smelled something that he didn’t like. I had had approached my stand that day from downwind–the opposite direction–so he couldn’t have smelled my ground scent. Then it hit me. He had crossed the path where I had approached the stand yesterday! He smelled my ground scent from 18 hour previous. The ability of a deer to smell danger is legendary, and it stands at a level that we humans cannot even comprehend. It is so far above our ability to smell, it’s hard to get a grasp on what their world must be like each day as they interpret the world around them with their nose. Fortunately, we know a lot more than ever about how deer smell. Let’s take a look at four things that give members of the deer family their amazing ability to smell what’s around them. The Long Snout Members of the deer family and predators need their sense of smell to survive, so they are equipped with far more olfactory receptors than those animals that do not rely on their sense of smell. The long snout creates more room for special nerve cells that receive and interpret smells. It’s estimated that humans have about 5 million of these olfactory receptors, while members of the deer family, including elk and moose, have about 300 million. Bloodhounds have about 220 million. Members of the deer family have something else going for them. Some of these olfactory receptors are specialized for certain scents. For example, research has shown that elk have certain sensory cells that are tuned into the chemical signature of wolf feces. It stands to reason that deer do as well. There is no scientific research to back it up, but whitetail deer may have receptors that specifically recognize the chemical signature of the bacteria that create human scent. Deer also have a vomeronasal organ (Jacobson’s Organ) on the roof of their mouth that adds another dimension to their ability to smell. This organ actually allows them to smell particles in the air that comes through their mouth. The Specialized Brain The area of the brain dedicated to interpreting scent is larger in deer than in humans. The drawing of air across all those receptors in the snout sends signals to the primary olfactory cortex, which is in the temporal lobe of the brain. Because this part of the brain is larger in animals that use their nose for survival, this creates an ability to interpret the smells that’s added to their ability to pick up all those smells with those 300-million receptors. This would suggest that using a cover scent of any kind would be futile, because a deer can simply sort the smells out. A hunter using deer urine to cover his scent smells like a hunter and deer urine to a deer, not just one or the other. While cover scents have little effectiveness, the ability to reduce human scent with antibacterial soaps, detergents and sprays, anti-microbial Scent Killer, and carbon is proven science. The science of the deer’s smell would suggest that reducing human odor is worth the trouble, attempting to cover it up is not. Smelling in Stereo Members of the deer family also have broader lateral nostrils which allow them to detect smells directionally. Moose have the most pronounced application of this. This allows the animals to determine the direction of the source of the smell more readily. This is called “stereo olfaction,” and it allows members of the deer family to more quickly determine the source of danger. You may have noticed a deer raise its head as it is smelling the air. The deer is flaring its nostrils while drawing air across the olfactory receptors in its snout. The animal can quickly determine what it’s smelling and the direction it’s coming from. They Live by Their Nose The fourth thing that helps members of the deer family survive is simply an increased awareness of the smells around them. We humans might not pay much attention to the scents coming in through our nose until it overpowers our other senses. We don’t think about smells much; until someone hands you a child with a dirty diaper, or you walk into a restaurant where they are frying bacon. Contrast that to the life of a deer, which is focused on the smells coming through the nose 24-7. The other four senses take a back seat to the importance of smell in their everyday lives. We humans can increase our awareness of the smells around us just by paying attention to them. Have you ever smelled a rutted up buck before you saw him? How about a herd of elk? Using our ability to smell what’s around us is a skill that can be developed. After all, we are predators at heart.